This project explores the tensions, assumptions and challenges of private land conservation in the context of neoliberal environmental governance.

The increasing popularity of private land conservation (PLC) globally has quickly translated into an array of polices and programs aimed at achieving ecological benefits. The growth of PLC is entwined with the rise of neoliberal governance, with private land proving congruous with the promotion of market-based instruments (MBIs) and the reliance on private protected areas for conservation in lieu of government investment in public lands. Despite a growing literature on the implications of neoliberal environmental governance, there remains a need for specific insights into the way that individual landholders and ecologies can co-opt or resist the rationalities of MBIs in the practice of private land conservation. Through semi-structured interviews and property walks with 18 landholders, this research examines the implementation of a reverse-auction tender scheme called ‘EcoTender’ in Victoria, Australia.

We uncovered four main tensions between the market logic of the program and conservation practice:

1) Some landholders used the payment scheme to increase regulatory protections on their property through covenants/easements . Seven of the landholders involved in this study had secured a covenant on their land through EcoTender, but four of those landholders had used this mechanism

in an manner that departed from the scheme’s intention. Rather than using the covenant as a means for enhancing the competitiveness of their bid and increasing the likelihood of receiving money to cover conservation work, these four landholders reduced the value of their bid as a way to increase the chance of getting a covenant. One participant explained the process of under-bidding to get a covenant:

“Oh, I just took a punt (on costing the bid), what I thought might get through, what it would cost, and what I was prepared to accept as a fair deal… I paid half of (the management costs).”

The covenant, rather than the money to cover management costs, became the ‘hook’ that enticed some landholders to participate.

2) Many landholders struggled to conceive of their stewardship practice as contractual labour. Of the 18 research participants, only five of the participants included the cost of their own labour as part of their bid. There was a strong sense that the labour of land management was the altruistic contribution that participants could provide as part of the conservation process. As one participant noted

“(The labour is) my part, you’ve got to put in yourself”.

This reveals the way that conservation practice is bound up with other expressions and experiences of land management, which might align more with intrinsic, recreational or even aesthetic motivations for doing conservation work.

3) Landholders were producing novel ecosystems that challenged land management focused at the property parcel scale when EcoTender encouraged a return to historical benchmark ecologies.

Many participants dealt with the challenge of managing plantings that had not materialised in the way they had intended. All but two research participants had a restoration component to their conservation work, so the ecologies that were emerging possessed a high degree of novelty. The types of novel outcomes included a failure of seedlings to grow, the dieback of new plantings and established plants around them, secondary infestation of weed species that had been cleared prior to planting, environmental change factors like drought or flooding and the grazing of plantings by native and introduced fauna. Another common experience was the spread of plants from adjoining properties through seeds blow through on the wind or washed over through flooding.

4) Many landholders wanted social collaboration when the program required competition for cost efficiency.

Eight landholders spoke directly and unprompted about the fact that they would like to meet other participants and have an informal network where they could contact each other. The central reason for wanting social connection was to gain some reassurance that they were not the only ones who were encountering challenges, difficulties or unexpected management outcomes from their activities (plants not growing, weeds returning, for example). One participant captured this feeling when describing the fact that it would be nice to have a sense of “shared experience” in EcoTender.

Our insights show that PLC must create room for a diverse trajectory of conservation practice in dynamic socio-ecological contexts. This means careful reflection on the validity of assumptions underpinning MBIs, the trade-offs that come with applying market logic to conservation and the long-term implications of these instruments for policy and practice.

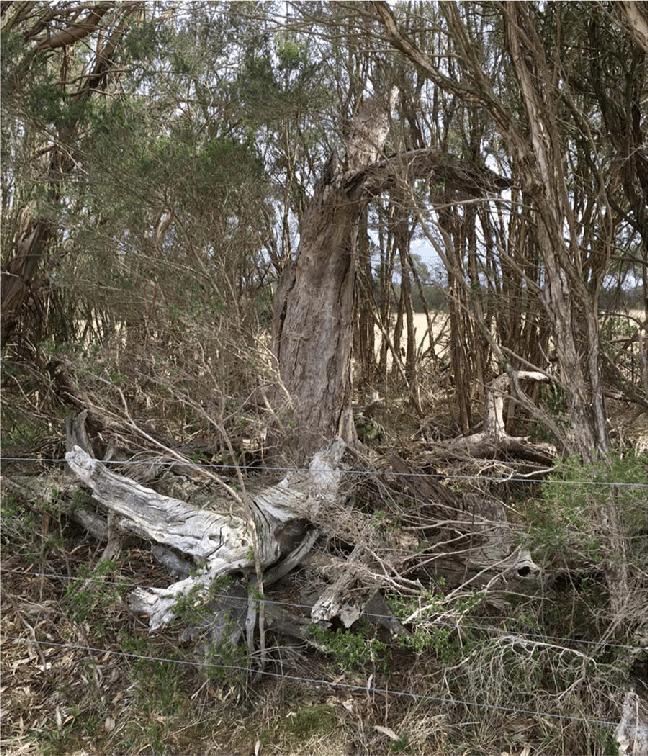

A small strip of linear remnant vegetation that has been covenanted through EcoTender.