Australia needs a bold national project to tackle the climate crisis and support households by shifting to a more sustainable housing industry.

Households across Australia are struggling with soaring energy and housing costs and a lack of housing options. Mixed with a climate crisis, economic volatility and social inequality, it’s a potent set of policy problems. Australia needs a circuit-breaker – a bold national project to tackle the climate crisis and support households by shifting to a more sustainable housing industry.

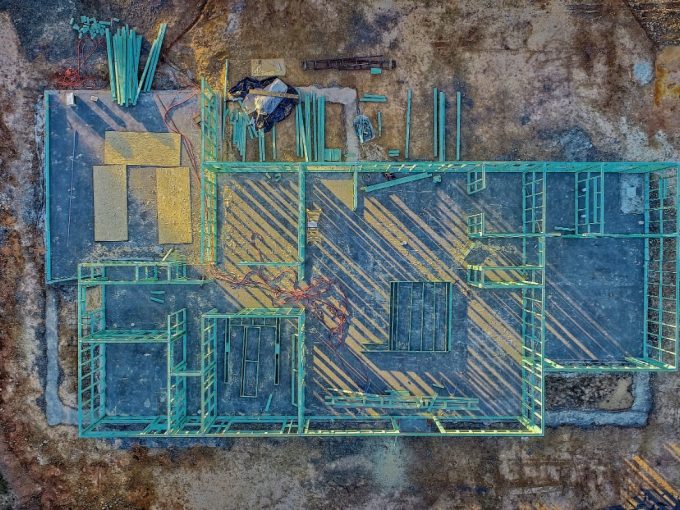

This is a project based on circular economy principles. The emphasis is on reducing materials and resources, optimising building lifespan, designing for reuse and zero waste, and regenerating nature. By getting the most out of finite resources, we can minimise waste and shrink our carbon footprint.

Our research for the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) applies these principles to housing. We developed a comprehensive strategy for the sector’s transition to a circular economy. It gives priority to local jobs, access to affordable housing, resilient and functional design, and carbon-neutral, energy-efficient operation.

Solving two problems at once

The circular economy offers answers to the dual challenges of housing affordability and sustainability. These solutions work across households, renters and owners.

Both the climate crisis and the human right to adequate housing demand urgent policy responses. Despite this, new energy-efficiency standards that the nation’s building ministers had agreed would take effect in October this year have since been delayed in a majority of states.

Standards are the key to unlocking the shift needed to deliver housing that is both affordable and sustainable. In combination with fiscal and financial policy frameworks, business support schemes and education and training, the housing industry can develop its capacity to embrace and exceed standards. Australian households and the planet will benefit.

How can Australia lift its game?

Housing policymakers across Asia and Europe are actively pursuing circular economy goals. As a result, Australia can learn from a wide range of circular economy approaches. Using better designs, techniques and materials, we can readily reduce the carbon footprint of our housing.

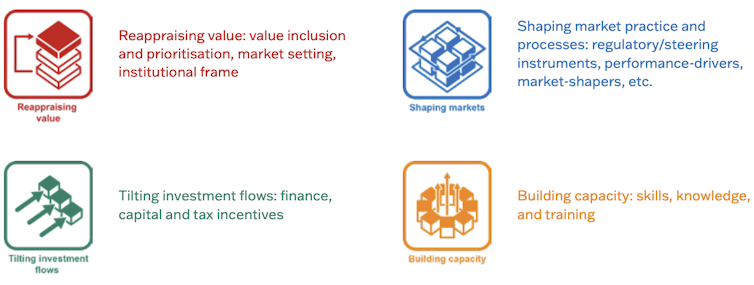

As the AHURI report details, a step change of comprehensive housing reforms that lead to more affordable housing and energy bills can also deliver greater resilience and social justice. The strategy identifies four areas of reform:

- assign a higher value to the sustainability of housing

- shift market processes

- tilt investment flows by providing incentives for circular housing designs and projects

- build the sector’s capacities to deliver sustainable outcomes.

Our research also recognises the specific forms of housing and the supply chains of materials to build them. These forms include residential neighbourhoods and precincts, new and renovated apartments, and social housing.

Internationally, we see a growing number of “eco-precincts” – walkable, sustainable, mixed-use developments. However, these are still seen as niche experiments, individual and not joined together across neighbourhoods.

Australian apartment building standards also leave much room for improvement. Robust and specific regulations to embed the circular economy in the construction, use and reuse of apartment buildings would provide clarity for the industry.

Apartment projects typically involve major developers and lenders. As a result, success with circular economy practices in this part of the housing sector can be a catalyst for adopting them more widely.

And because a high proportion of apartments are rented in Australia, higher energy standards for rental properties can help counter increasing energy poverty.

In social housing, tenant preferences are rarely considered in sustainable retrofits. Circular economy retrofitting delivers benefits for both landlords and tenants, through better design and lower bills.

Energy efficiency and alternative energy technologies have largely driven sustainable retrofit activity in Australia. Less attention has been paid to other circular economy housing priorities. Much more work must be done to extend housing lifespans and ensure passive design as standard practice, drawing on natural sources of heating and cooling such as sunshine and ventilation.

We lack adequate data tracking material stocks and flows through the housing sector, including for retrofits. This applies to both new and recycled/reused materials in the construction and demolition waste streams.

Our analysis shows the use of concrete in housing continues to increase. This means concrete-related emissions are increasing too. Better data systems to track material flows would give us a clearer picture of where to target efforts to reduce embodied carbon in housing.

Towards a national strategy

Radical decarbonisation is needed. It won’t happen without big shifts in practices and materials.

Circular economy housing is a social project as much as a regulatory reform. Success depends on buy-in to the whole process across all levels of government, civil society, private sector and education and training institutions.

Simply relying on market demand to drive the supply of circular goods and services neglects the nature of current supply chains and the weakness of consumer voices. In particular, the one in three households that are tenants have little say in how sustainable their housing is. Stronger partnerships between governments, private developers and local communities are needed to deliver the scale of change required.

The housing industry can step up, with the support of policy incentives, to embrace leading circular economy practice. Housing has a big role to play in the economy-wide changes needed to achieve sustainable use of materials and net-zero emissions.

Ralph Horne, Associate Deputy Vice Chancellor, Research & Innovation, College of Design & Social Context, RMIT University; Julie Lawson, Adjunct Professor, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University; Louise Dorignon, Vice-Chancellor Postdoctoral Research Fellow, RMIT University, and Trivess Moore, Senior Lecturer, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Story: Ralph Horne, RMIT University; Julie Lawson, RMIT University; Louise Dorignon, RMIT University, and Trivess Moore, RMIT University